Liturgical Mindfulness in a Dynamic Church

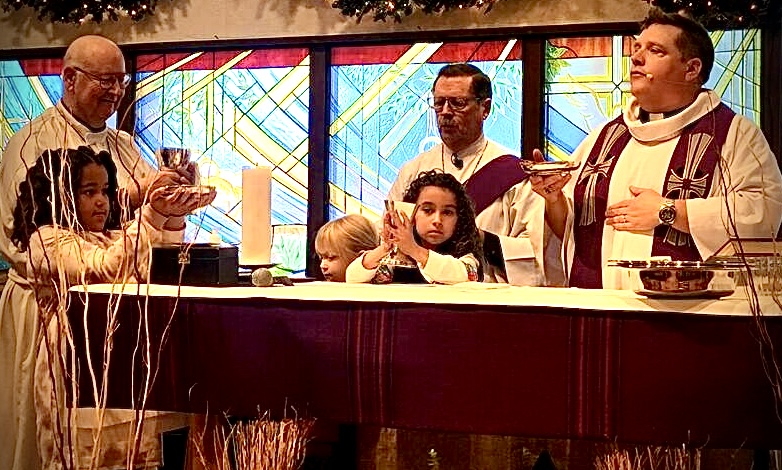

Worship in the Episcopal Church takes place during something called a liturgy. This is not unique to the Episcopal Church. Our Christian cousins in the Latin Rite, the Orthodox Rite, Lutheranism, and a number of other denominations also practice liturgical worship. When we think of liturgy, any number of images might pop into our heads. We might picture candles, elaborate vestments, highly decorated books, incense, holy water, bread, wine, books, music, and more. And while all of these are indeed components of liturgical worship, there’s something that is absolutely necessary for a liturgy to take place. In order for there to be a liturgy, there must be people present.

The English word liturgy comes from the Greek word leitourgia, which means work of the people. Yep. Even though we might think of all kinds of elaborate actions or objects when we think of a liturgy, the most important piece of liturgical worship is the people. If we think about it, then it actually makes a lot of sense. How many times have we wandered into a church that was different from our home place of worship? When we have, we probably noticed that churches all do things at least a little differently. We might notice different expressions of music. We might see that the priest wears different vestments than we see at our home church (or maybe no vestments at all!). We might see a big, professional choir when we’re used to a smaller, community choir. We might notice the use of incense every Sunday when we’re only used to using it for special occasions. We might see an elevated, decorated pulpit when we’re used to seeing a smaller, simpler one at home. And even if these expressions of worship might feel a little different, they are all valid expressions of worship as long as one thing is consistent: the presence of people.

Because of this definition, it really isn’t appropriate for priests to preside at Eucharistic celebrations without anyone present. This isn’t to say it isn’t possible for a priest to consecrate the elements alone (remember, it’s God who makes the consecration take place and we don’t limit the power of God). It simply doesn’t make a lot of sense for a Eucharistic celebration to take place without people there. Certainly, there are varying circumstances that come into play. For instance, if a corporate liturgy is scheduled and no one shows up on time, the priest might have to decide between starting alone in case someone does show up late, or simply waiting to start until there happen to be people present. But the intention in that case is that the people were invited and that they will be present. If a priest decides to celebrate Eucharist alone with no intention of having others present, then that’s a little more difficult to justify. People make liturgy happen, and the Eucharistic prayer is not complete until the people, however many are present, respond with the Great Amen at the end of the prayer.

We are approaching the season of Christmas, which is one of the most highly attended days on the church calendar. It’s very common to hear snickering about the “C and E crowd,” referring to people who attend church only on Christmas and Easter. But I want to advocate against making these kinds of comments. Instead, I’m hopeful that we liturgical Christians can embrace the presence of visitors without placing any judgement (positive or negative) on how often we perceive their attendance. Firstly, it isn’t really anyone’s business how often someone else attends church. Secondly, if people are in church, that only makes liturgy better. If liturgy is the work of the people, then the presence of more people means a more joyful celebration. Instead of making passive-aggressive comments, it is important that we welcome our visitors on Christmas, regardless of how often they attend.

Higher attendance numbers on holidays such as Christmas and Easter tell us that liturgy is important to people. It is comforting. It is soothing. For many people who grew up practicing in a liturgical faith tradition, the Christmas liturgy is simply part of their whole picture of the Christmas holiday. Maybe they remember their childhood, when they attended midnight mass and then returned home to rush to bed so they could ensure Santa Claus would visit in the early morning hours. Maybe they remember attending with a beloved family member who is no longer living, and they’re comforted by the memory. Maybe they’ve lost a loved one during the year, and attending a liturgy helps them to feel some peace in their time of grief. Maybe they just like to attend Christmas services and there isn’t actually an articulated reason for why. Whatever the case, people in church is a good thing. As much as I’d like to think of myself as one of God’s favorites because of my regular attendance at church, this simply isn’t the case. God loves all of us, no matter how often or infrequently we attend church. We can’t earn extra “Jesus points” for attending more frequently, and we can’t lose points by skipping a Sunday.

When liturgies take place at a church, it is important that they are scheduled to meet the needs of as many people as possible. As the Church continues to change, this means we need to stay creative about how to continue to make meaningful liturgies. While some people connect well to Eucharistic liturgies, other people might find the rituals confusing or even frightening. And this isn’t something new. Years ago, when Protestants and Catholics frequently feuded with one another, Protestants made fun of Catholic ritual and Eucharistic theology. I’m sure you’ve heard of the “magic words” hocus pocus. Did you know that these “magic words” were first used to belittle Eucharistic theology? In Latin, the words “hoc est corpus meum” mean “this is my body”. Early Protestants decided that it looked like Catholic priests were performing some kind of magic trick during the Eucharistic prayer, so they said “hocus pocus” must be the magic words. Certainly, when we do catechesis (another Greek word that means instruction), we can help to alleviate some of this fear and discomfort. But it takes time and effort. These days it is becoming more common to experience liturgies with modern music, a shared homily, and even scripture readings with no celebration of the Eucharist. Fortunately, our Anglican theology teaches us that the Body of Christ is present not only in the Eucharistic elements, but also in the people gathered and in the Word of God as proclaimed through scripture.

Liturgy is important to the history of the Church. I am a lover of good liturgy, which can be a teaching opportunity in and of itself. It is also a terrific tool for providing pastoral care. If someone is in need of healing prayers, liturgy can bring great comfort and relief. It can also bring us assurance of the forgiveness of our sins, real encounters with Jesus Christ and his people, and contentment in the reciting of familiar words and songs. But it doesn’t fit neatly into a box. Liturgy that works well in one setting might not work too well in a different one. Fortunately, we get to be creative. We get to listen to each other and to design liturgies that are meaningful and fulfilling to as many people as possible.

As we complete this Advent season and move our way into Christmas, let’s try to look at liturgy critically. What do we notice about the ways liturgy speaks to us? What are our assumptions and expectations when it comes to a liturgy? Do we have biases that lead us to the conclusion that liturgy “should” be done a certain way? What might it be like for us to allow ourselves the freedom of moving outside our comfort zones and trying something a little different? All of these questions are important, and they’re useful in our faith lives. As we do this interesting work, may we continue to be mindful that not all of us share the same liturgical backgrounds, and it’s important to meet people where they are. If you are a regular liturgical worshipper, offer a kind word of guidance to someone who might be visiting. Ensure people feel welcome, even if you suspect they are only here for Christmas. Continue to pray for those who are not in the pews every week. And continue to enhance your own spiritual life so that your own understanding and appreciation of liturgy can continue to grow and develop.