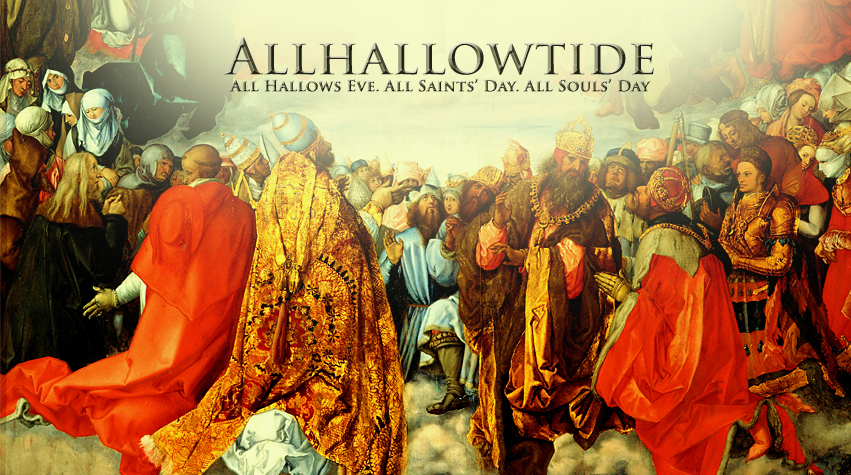

Now that we have entered the first part of the month of November, we find ourselves in something called Allhallowtide. While technically including only the days of October 31 through November 2 every year, our Book of Common Prayer gives us a little extra leeway to continue the celebration of Allhallowtide through the first Sunday in November. All Saints’ Day, November 1 every year, is a principal feast in the Episcopal Church. Because it is so important, the Church makes allowance for us to transfer the feast to the first Sunday in November whenever November 1 does not fall on a Sunday. We are only given permission to transfer up to two feast days to Sundays each year: All Saints’ Day and a parish’s patronal feast day. The second is true only if the patronal feast day doesn’t fall during the seasons of Advent, Christmas, Lent, or Easter. Our permissions surrounding All Saints’ Day are therefore unique!

So what’s the big deal about All Saints’ Day? The answer is, it celebrates all of us and our relationships with God. While there are varied understandings of what it means to be considered a “saint”, the word comes to us from Latin, and it means “holy”. A saint is someone who is holy. Certainly, different denominations have prescribed ways of identifying saints. In Roman Catholicism, for instance, the saints are people who have died and have gone to heaven. There is a strict and complex process for canonizing saints. This process involves a literal trial with attorneys and everything. Have you ever heard of the devil’s advocate? This is a real occupation in the Roman Catholic Church. It’s someone who argues against a person’s canonization. And in the Roman Catholic Church, All Saints’ Day is a day to celebrate the saints who have been canonized, and the saints who have not. It’s a feast day celebrating everyone who is in heaven. For the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the saints are the members of that church. We are living in what they call the “latter days”, and members of the LDS church are the “Latter-day Saints.” In Anglicanism, we have a little broader understanding of the communion of saints. Each of us is called to be holy. While some Anglicans will still tell you that a person must be in heaven to be considered a saint, many others will tell you that we are all saints—holy—by virtue of our baptism. This is one of those situations where there isn’t exactly a right or a wrong belief. But if the word saint means holy, then we’re all called to be saints. That’s true whether we’re still alive or now deceased.

So what exactly do we mean when we say “Allhallowtide”? Well, like the word saint, the word hallow also means holy. It comes to us from Old English. Think of the Lord’s Prayer. We say, “hallowed be thy name.” In other words, “your name is holy”. And in Old English, the day we remember all the holy people was called All Hallows’ Day. The words hallow and saint mean the same thing, they just entered our lexicon from different languages. And just like Christmas Day has a Christmas Eve, and New Year’s Day has a New Year’s Eve, All Hallows’ Day has an All Hallows’ Eve. A day’s eve, again coming from Old English, means the day before. In Old English, All Hallows’ Eve was known by the contraction Hallowe’en, short for Hallows’ Even or Hallows’ Eve. Yes, this means Halloween is a religious holiday. No, Halloween is not “of the devil.” And, contrary to what staunch atheists will tell you, no, Halloween did not come from a Pagan festival. While it’s true that there is crossover between religious and secular observances, celebrating the saints is what Allhallowtide is about for Christians. Trick-or-treating, dressing up in costumes, and carving Jack-o’-lanterns all have roots in celebrating the eve of All Saints’ Day.

When we talk about a tide, we’re talking about more than one day. Eastertide, for instance, lasts for 50 days. Christmastide lasts 12 days. Allhallowtide is essentially the end of October and the first part of November. It includes Halloween, All Saints’ Day on November 1, and All Souls’ Day on November 2. All Saints’ and All Souls’ have become conflated by many Christians in recent years, but they’re not the same thing. All Souls’ Day, also known as the Feast of the Departed, is a day to remember everyone who has died. While we never know where a deceased person ends up (heaven or somewhere else?), we do believe every human person has a soul that lasts for eternity. On All Souls’ Day, we pray for all the departed, even for those who may not be saints in the traditional sense.

Allhallowtide reminds us of a few different things. Firstly, we are reminded that we are holy. We are made in the image of God, and if God is holy, then he made us holy. Secondly, it reminds us that we will someday die. While there are different traditional liturgical colors used on All Souls’ Day, two options are black or purple (also called violet). These colors are associated with death and mortality, which is why they often make appearances during the seasons of repentance: Advent and Lent. Whether we like it or not, we are going to die. There are nearly eight billion people on the planet right now, and each of us will one day die. Each of us will one day be amongst those prayed for on the Feast of the Departed. And although we can sanitize death and call it something else like “passing away”, “crossing over”, or “moving on”, death is a part of life. Changing the name of death does not take away its power, even if it makes us a little more comfortable.

How did you feel while reading that last paragraph? Were you scared? Were you intrigued? Were you angry? Were you feeling contemplative? Were you sad? There isn’t a wrong answer. You felt what you felt. And it’s good to explore those feelings. If you felt scared, don’t run from the feelings of fear. Explore them! If you were sad, explore your feelings of sadness. If you were angry, explore your feelings of anger. Why explore? Because we can learn so much about ourselves if we’re willing to explore our emotions. Too often, society teaches us to hide our emotions so that we don’t make other people uncomfortable. But if someone else is uncomfortable about our feelings, then that’s their problem.

The truth is, although we certainly believe we are holy and we definitely believe that we are on a path toward heaven and eternal life, none of us has seen the other side of the veil. None of us has experienced death yet. And while our faith gives us some images about what we might anticipate after death, we haven’t actually been there yet. We simply don’t know. And if we acknowledge that we have doubts about what death will look like, does that mean we’re frauds in our faith? No! As Anne Lamott says, the opposite of faith is not doubt. The opposite of faith is certainty. Our faith is not perfect, and an imperfect faith does not mean we have imperfect relationships with Jesus. Is it sinful to have doubts about the mysteries of Christianity? Is it sinful to have doubts about how Jesus can be present in the sacrament of the Eucharist? Is it sinful to have doubts about what death is going to be like? Absolutely not. We’re not expected to blindly believe things without using some critical thinking. But our faith is like a muscle, and muscles become stronger when we exercise them. Our faith becomes stronger when we practice it. Does working out everyday lead to perfect fitness? Not necessarily. Does practicing faith everyday lead to perfect faith? No. But both contribute to our stronger, healthier selves.

As we celebrate the rest of this Allhallowtide, let’s remember to give thanks for the lives of all those people who have gone before us. We pray for those who believed in God, those who did not, and those whose faith was tested. We pray for those who agreed with us and for those who did not. We pray for those who made mistakes and for those who did a lot of things right. We pray for those whom we perceived to be holy and for those whom we perceived to be not so holy. God is bigger than anything we can ask or imagine. His mercy and his love extend far beyond anything we can comprehend. His mercy is great for those who don’t believe and for those with difficulty believing. His love is great for those who love him and for those who do not even know him. Each of us is made in God’s image and each of us is made holy. Allhallowtide reminds us that we can embrace our sacredness and dwell in communion with God and with his people. We are called to be saints. We are called to be holy. Allhallowtide is our time to be ourselves and to acknowledge our relationship with a loving God.